Hello friends!

We’re back with another instalment of IEM theory. This week, we are going to discuss the concept of Gifting and Gaining (G&G) and an example of it in practice.

G&G is a concept that reframes ‘losses’ for stakeholders as ‘gifts’ and defines ‘gains’ as positives that can be enjoyed and shared by stakeholders and the environment. The concept frames trade-offs as acceptable losses for the greater good. It demonstrates the importance of framing and the impact it can have on environmental management.

The concept of G&G has been a part of several environmental management projects, such as the development of the Kaikōura Marine Reserve. The Kaikōura Marine Reserve was first proposed off the back of a nationwide campaign encouraging the increase of marine reserves in Aotearoa New Zealand’s waters. The aim of the campaign was (and still is) to have 10% of the country’s coastal-marine environment in reserves. A marine reserve operates as a conservation tool, protecting all components of a marine ecosystem, helping to conserve biodiversity and allowing ecosystems to return to a more natural state (DOC, n.d.).

Forest & Bird submitted a proposal for a marine reserve on the Kaikōura Peninsula in 1992 (which did not eventuate). The proposal generated debate amongst stakeholders in the area – commercial and recreational fishers, iwi, local authorities, and the community. The significance of the area, overfishing issues and the appropriateness of the proposal were at the forefront of discussions. As there was no coordinated institutional or policy response to these concerns, there was no process to develop a problem-solving framework. A lack of exploration into other options resulted in people falling into a ‘goal trap’.

G&G was applied to address the environmental problems through the consideration and understanding of multiple stakeholder perspectives. This problem framing (Bardwell, 1991) considered social, cultural, economic and environmental concerns (TKTTM, 2011). This process facilitated the collaborative environment for discussions that generated consensus amongst stakeholders to work towards a common goal (Margerum and Born, 1995).

Eventually, a marine reserve was established in Kaikōura. With the framework of G&G, the impasse between stakeholders and iwi was addressed. G&G became a part of every discussion and other barriers (Cairns, 1991) such as non-statutory plans for Kaikōura’s coastal resources were developed.

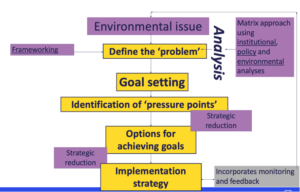

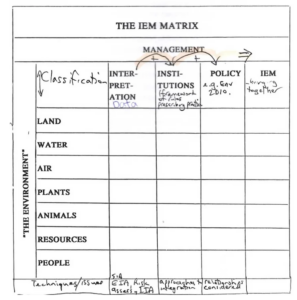

G&G is most effective in the solution space of the IEM process, as it can guide the identification and implementation of resolutions to environmental problems. While G&G is beneficial, it is still faced with several barriers to widespread implementation (Borrie et al., 2020).

References

Bardwell, L.V. (1991). Problem-framing: A perspective on Environmental Problem-Solving. Environmental Management, 15:603-612.

Borrie, A., Brown, I., Butterfield, K., Driver, T., Gear, S., Nevin, S., Shirley, L., & Wijesinghe, R. (2020). Gifting and Gaining: Theory, Application, and Linkages with Integrated Environmental Management. https://www.learn.lincoln.ac.nz

Cairns, J. (1991). The Need for Integrated Environmental Systems Management [book chapter]. In Cairns, J. and Crawford, T.V. (ed.), Integrated Environmental Management. Lewis Publishers

Department of Conservation (DOC). (n.d.). Type 1 Marine Protected Areas – Marine reserves. Department of Conservation. https://www.doc.govt.nz/nature/habitats/marine/type-1-marine-protected-areas-marine-reserves/purpose-and-benefits/

Te Korowai o Te Tai ō Marokura (TKTTM) (2011). Te Korowai: Strategy. http://www.manu-ao.ac.nz/massey/fms/manu-ao/documents/Te%20Korowai%20Strategy%20- %20JPirker.pdf?0706724C78B9E36CF719A3C36253FFD7.

Margerum, R.D. and Born, S.M. (1995). Integrated Environmental Management: Moving from theory to practice. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 38(3).