Gidday team,

The Stuff news article “Beef and sheep farmers call for limits to carbon farming” came to my attention as part of preliminary research for my group project this semester. Having since undertaken further research of published material, grey literature and contemporary media, I have learned more about this complex issue.

The Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) is Aotearoa New Zealand’s main tool for reducing carbon emissions. The country has domestic and international climate change targets (Ministry for the Environment, n.d.) but the activities to reach these goals are having unanticipated effects. The primary reduction plan is through afforestation.

Massive land use change off the back of afforestation is predicted to negatively affect rural communities socially, culturally, economically and environmentally. The social impacts include reduced employment (BDO New Zealand Limited, 2021), loss of communities, fire risk and schools (Flaws, 2020). Cultural concerns include loss of indigenous biodiversity and challenges in finding ways to maximise return on marginal land, without compromising Māori values (EDS, 2021; Mercer, 2021). The economic impacts include loss of employment in the area and environmental concerns surrounding the alterations to indigenous ecosystems (Bellingham et al., 2022; Rundel et al., 2014), wilding pines, pests, and changes to catchment hydrology risk downstream from sedimentation loss and erosion when felling trees (New Zealand National Film Unit, 1976).

Sheep and beef lobby group Beef & Lamb NZ commissioned a report to validate the amount of land that has been or will be planted into exotic plantation species in the near future that is likely to make land out of pastoral production. This report identified that “a significant amount of productive sheep and beef farmland has been converted to forestry over recent years, reinforcing the need for limits on carbon farming” (Morrison, 2021). The large shift of productive land to exotic forestry has implications for other parts of the industry, such as processing companies and those supplying services. Beef & Lamb NZ are asking for the Government to work with the sector to introduce limits on forestry offsets.

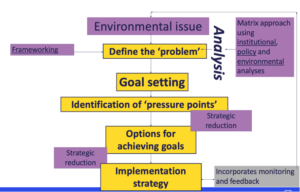

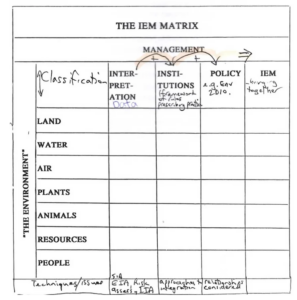

There appears as though there is a disconnect between the policy space and the institutions at play. The discussion about what action Aotearoa should take, changes depending on who one engages with. Carbon farming is a complex issue that must be investigated using an IEM approach that takes a holistic view of the problem. Those partaking must appropriately define the environmental management problem (Bardwell, 1991), before setting adaptive goals with key stakeholders as it is important to critically analyse the issue from an interdisciplinary perspective. Those partaking must identify key process steps which will lead to IEM. Following an IEM-based process promotes effective outcomes.

Aotearoa’s carbon emissions and proposed solutions are complex. It will take a lot of collaborative, considerate, holistic and productive discussion and action to ensure future solutions are the best they can be for all involved.

References

Bardwell, L.V. (1991). Problem-framing: A perspective on Environmental Problem-Solving. Environmental Management, 15:603-612.

BDO New Zealand Limited. (2021). Report on the impacts of permanent carbon farming in

the Te Tairāwhiti region. Tairāwhiti Economic Action Plan Operations Group. https://trusttairawhiti.nz/assets/Uploads/Impacts-of-permanent-carbon-farming-on-the-Tairawhiti-region-July-2021.pdf

Bellingham, P. J., Arnst, E. A., Clarkson, B. D., Etherington, T. R., Forester, L. J., Shaw, W. B.,

Sprague, R., Wiser, S. K., & Peltzer, D. A. (2022). The right tree in the right place? A major economic tree species poses major ecological threats. Biological Invasions. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-022-02892-6

EDS. (2021, September 16). Carbon farming with pines bad for the environment. EDS.

https://eds.org.nz/resources/documents/media-releases/2021/carbon-farming-with-pines-bad-for-the-environment/

Flaws, B. (2020, June 14). Rural communities under threat from carbon offsetting, farmers say. Stuff. https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/farming/121720901/rural-communities-under-threat-from-carbon-offsetting-farmers-say

Mercer, L. (2021). Beyond the dollar: Carbon farming and its alternatives for Tairāwhiti Māori landowners. https://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10063/9443/thesis_access.pdf?sequence=1

Ministry for the Environment. (n.d.). New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme. Ministry for the Environment. https://environment.govt.nz/what-government-is-doing/areas-of-work/climate-change/ets/

Morrison, T. (2021). Beef and sheep farmers call for limits to carbon farming. Stuff. https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/farming/agribusiness/125958601/beef-and-sheep-farmers-call-for-limits-to-carbon-farming

New Zealand National Film Unit. (1976). The Erosion of Our Land. www.Youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DjXJhQuPQfU

Rundel, P. W., Dickie, I. A., & Richardson, D. M. (2014). Tree invasions into treeless areas: Mechanisms and ecosystem processes. Biological Invasions, 16(3), 663–675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-013-0614-9